A policeman holds a thick rope in his hand and pulls behind him a man with a noose around his neck and a sign on his chest that reads “Five Columns” and “Traitor.” Behind him walks a violent crowd of people from Skopje, who hit, curse, and throw objects at the unfortunate man. This is how the enemies of the people were treated after the war.

And what did you do? I asked the president. The sight was so unpleasant that I went straight to Lazo Kolishevski with a request to stop this practice.

Did you really stop, I wonder today? I remembered this when, in a TV show seventy-six years later, the participants in the debate – a Macedonian history professor, a young researcher, a Macedonian, an American, and a journalist – my former student, listed several names of “five colonists” in Macedonia today. . Among them I heard his name. The topic, of course, was the dispute over history with Bulgaria, and just like a year ago, when the same journalist shattered my life with a two-second clip from my interview on Bulgarian television, I felt, to put it mildly, unjustified.

My democratic education, which I pass on to my students, says that there are no traitors in political dialogue in a liberal-democratic society. There can only be patriots on both sides of the debate. No one has the right to call his opponent a traitor or a fifth columnist just because he thinks differently.

There are only different opinions, different historical narratives, which should be freely expressed. If this thing does not happen, then the state is stagnant or going backwards because it is deprived of its main tool for progress – critical thinking. If we do not realize this very quickly, in repeating this international dispute, as we have with Greece for three decades with an EU Member State, we will get nowhere.

We must learn not to put at least labels, to listen to each other and to quote Gligorov again: Macedonia is a complex formula.

We are bothered by the different opinion and we seek salvation from the Macedonian historians, believing that there is some monolithicness for some common Macedonian world historical narrative. Exactly the opposite. Some of our historians find the beginnings of our Macedonian nation among the ancient Macedonians, others in the Middle Ages, and others in the middle of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. The former, for understandable reasons, will never accept the Prespa Treaty with Greece. The latter will never give up Samuel and his kingdom and will be against the Treaty of Good Neighborliness and Friendship with Bulgaria. The third closest to the truth are few.

I want to say that if we know that among historians, as well as in society as a whole, there is the same undemocratic spirit and the colleague can be defined as a traitor, it becomes quite clear how much we need the liberal spirit of tolerance between narratives.

This spirit is missing everywhere, even in music, as it became known with the brilliant Vasil Gavranliev, to whom I wish success at Eurovision. It is also missing at the highest level. Incumbent President Stevo Pendarovski said our country is unable to solve any major problem without foreign participation. This, of course, is a great shame for party leaders, but also for him personally. This is a shame for us as citizens as well. But this only confirms that there is a lack of democratic thinking in Macedonian politics, as well as among journalists and historians. Are foreigners the solution?

If we include foreign mediators in the Macedonian-Bulgarian dispute, which will not happen until the interests of the big countries are threatened, ie. NATO, then they will consult with their historians, who will brief them not on our or Bulgarian, but on Western political and historical literature, which is closest to the historical facts.

In such a conversation, some things we will hear we will like, others not. That the Macedonian nation and language exist and not only that no one should deny them, but on the contrary everyone should treat them with respect. As allies in the great anti-fascist struggle during World War II, together with the rest of the Yugoslav peoples, we have lasting and unbreakable ties. But also that, in the Balkans, there are only two countries that do not have a medieval historical heritage, but are modern, contemporary countries: Slovenia and Macedonia. They will also explain the pan-Bulgarian idea and how geopolitics has accelerated the creation of the Macedonian nation since the mid-19th and especially in the 1930s and 1940s.

As for Cyril and Methodius, they will first explain to us that throughout Europe, literacy and Christianity spread from the bustling cities of Venice, Dubrovnik or Thessaloniki, from the economic and cultural centers to the interior. Thus, both Macedonians and Bulgarians will understand that the holy brothers were in fact primarily Byzantine officials, not Macedonians or Bulgarians. Maybe then we will finally understand where the similarity between the Greek alphabet and our Cyrillic alphabet comes from and we will stop arguing whether we or the Bulgarians are the cradle of the Slavic civilization. But none of this will happen, because in the world of states, everyone explains things to themselves. Helping yourself is a basic rule of international politics, as experience with vaccines shows.

Realizing this and feeling the attack of the Bulgarian tornado, with texts from two decades ago I wanted the Macedonian society to start a dialogue with itself on this sensitive issue of identity. A year ago, in a text in Plusinfo, I sounded the alarm. I recognized the storm on the horizon and thought that the roof of the house was being repaired when the sun was shining. To protect it, we had to adapt Macedonian history to the new times. Unfortunately, we did not do that and the storm caught up with us.

Why? Read again the story of President Gligorov from the beginning of the text and you will easily conclude that no normal person wants to be in the role of this unfortunate man. Nationalism still rules the Balkans.

—————————————————

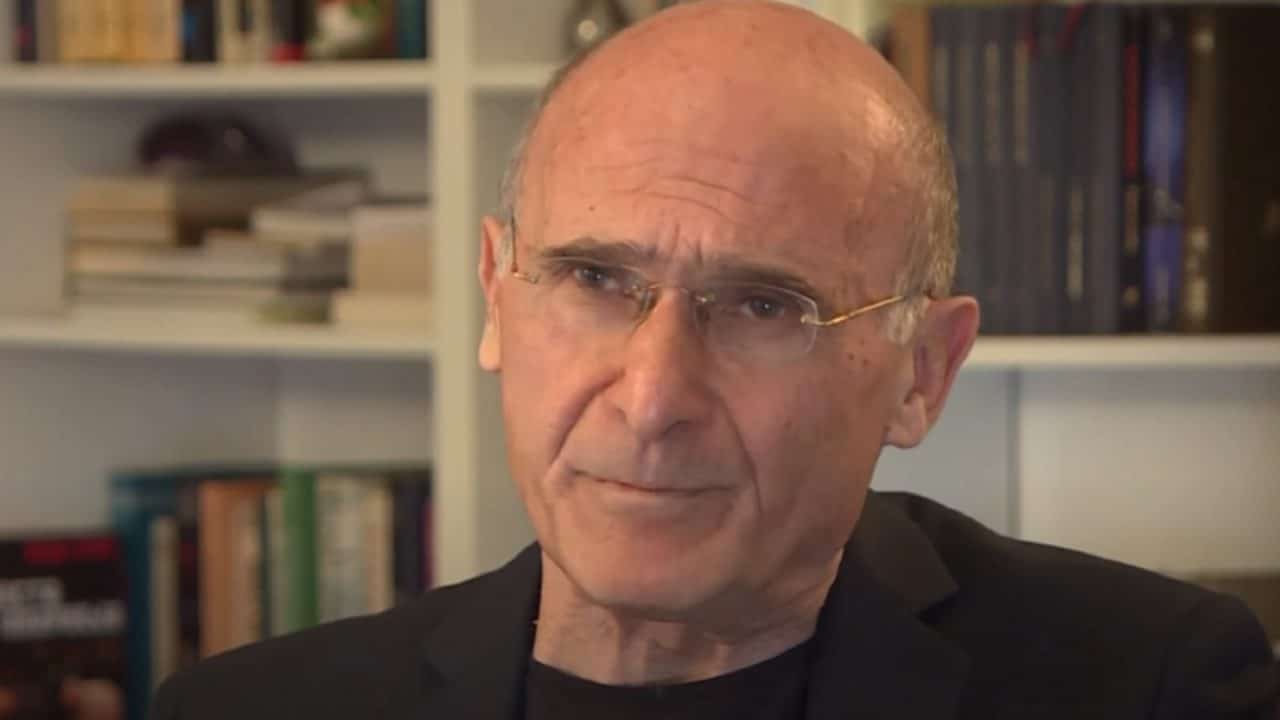

Comment by Denko Maleski, the first foreign minister of independent Macedonia. When the dispute with Greece arose, Malevski publicly called for a speedy resolution. In the spring of 2019. after writing that we were one nation and Gotse Delchev was a Bulgarian, he was subjected to a public lynching, reminiscent of the times after 1945, when everyone with a different opinion was persecuted and anathematized. President Stevo Pendarovski immediately fired him as an adviser “due to reduced budget funds”. Maleski is a professor of international relations at the University of Skopje. His analysis was published in Plusinfo.