A sea of Bulgarian buses parked in front of a market in the historic Turkish city of Edirne is exposing the scale of the currency crisis, which is blocking President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s path to the third decade of rule.

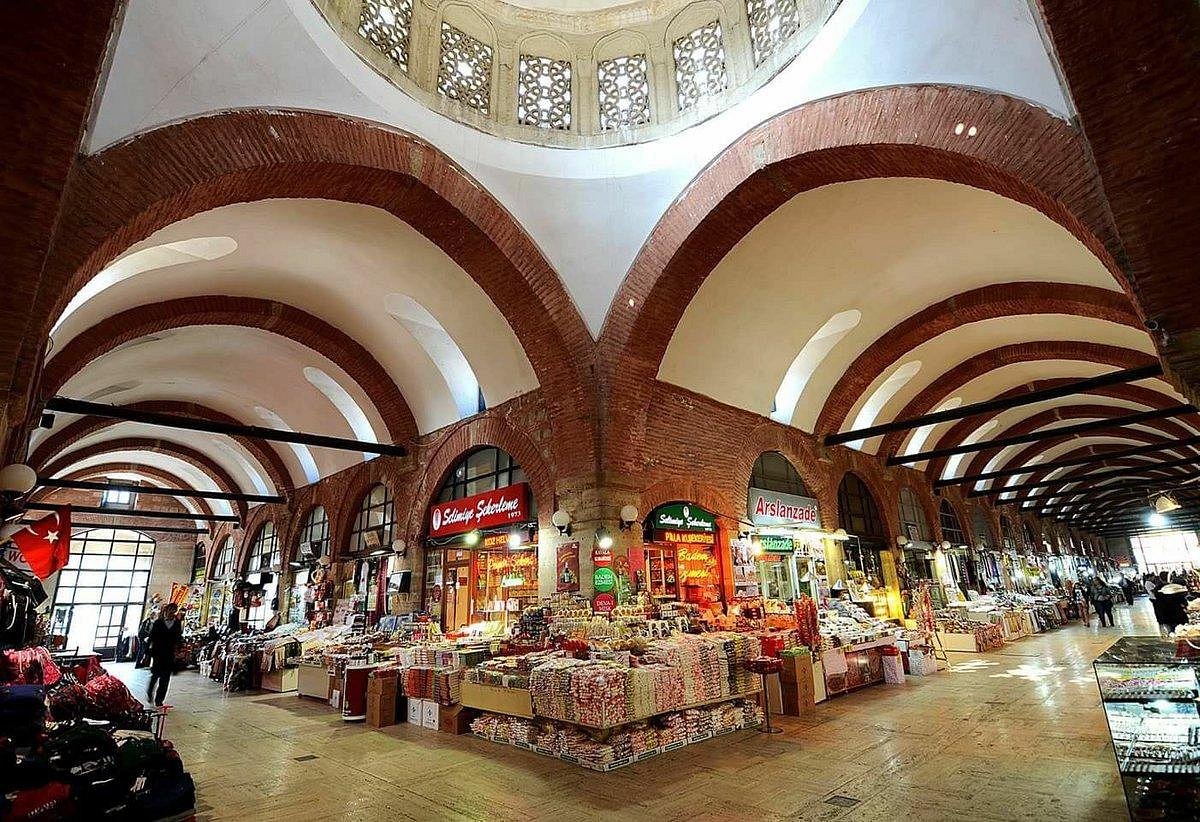

The mosque-filled city in the western part of Turkey was the early capital of the Ottoman Empire as it expanded into the Middle East and Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries. Now, this is where buyers from Bulgaria and the Balkans – one of the poorest countries in Europe – go to stock up on everything from lingerie to walnuts to a fraction of their price in Bulgaria.

“For us, the crisis is good, but for the Turkish people it is very bad,” said tour guide Daniela Mircheva before boarding a bus back to her hometown of Yambol, Bulgaria. “We were in a similar situation maybe 10, 11, 12 years ago,” Mircheva, 49, said, referring to the global financial crisis of 2008. “It’s very difficult.”

“Half lower price”

The troubled Turkish lira collapsed under the weight of Erdogan’s unusual economic experiment in an attempt to boost support ahead of the mid-2023 elections. Erdogan urges the central bank to cut interest rates, strongly believing that this will finally cure the chronic problem of inflation in Turkey. As all economists predicted, this led to the exact opposite. Consumer prices have risen by more than 20% a year. Some economists believe that this pace may accelerate in the coming months.

Since the beginning of November alone, the lira has lost a third of its value. It had begun to lose five percent a day until Erdogan announced new measures to support the currency on Monday, which managed to stop the landslide. This means that Mircheva can afford to load a few extra bottles of sunflower oil on her bus full of Bulgarian buyers.

“It is half cheaper than in Bulgaria. For us it is much cheaper, much more,” she said.

But the mood among Turkish market traders is bleak.

“Humiliating”

“It’s humiliating,” says Gulsen Kaya behind his counter, full of sweaters and winter clothes. “Look what he did to Turkey!”

Erdogan is betting that the cheap pound will lead to export-driven growth that will put Turkey on the path followed by China during an economic transformation that lifted millions out of poverty and created a new middle class. Erdogan advocated for the poor when he brought to power his party with Islamic roots in 2002, against all odds. He then surprised many by opening Turkey to foreign investment and sparking almost a decade of strong growth.

Economists and diplomats, as well as some Bulgarians, are trying to understand why Erdogan has decided to change course so dramatically in recent years.

“I think that the people who rule Turkey, if they do the things I think they should do, then the lira will return to the levels it was in the summer, very, very quickly,” said Bulgarian buyer Tinko Garev. “I am very sad for the Turkish people because I realize what these lower prices mean to them.”

A senior Western official said the drop in Erdogan’s rating in most opinion polls to 30% had put the veteran leader “in a state of political survival”.

“You can choose not to believe (in individual studies), but the trajectory is clear,” said the anonymous spokesman. “He is at the bottom of his support.”

“We are in shock”

Bulent Reisoglu has led the Edirne market since it opened after moving from its original location in Istanbul 15 years ago. He says the number of weekly shoppers filling its hangar-like mall has risen from 50,000 to nearly 150,000 since the full impact of the crisis.

“The number of foreign buyers has increased four or five times,” Reisoglu said.

However, traders earn less money as additional sales are more than offset by the deep collapse of the lira.

“Suppliers send us new price lists every week,” complains Utku Bitmez, a market trader. “All raw materials come from abroad, from Europe, China, and Italy,” he said. “The price of these products has doubled since last year.”

Reisoglu said he was watching traders nervously follow the latest exchange rates of the TRY on their phones.

“We are in shock,” said the market manager. “No one expected such a big devaluation.”

Bulgarian buyers also seem to have mixed feelings about such lucrative deals.

“Local people can’t buy all these things,” says Ilyana Todorova as she shopped to buy clothes for her teenage daughter. “It’s not good for ordinary people.”